BURKINA FASO & GHANA: The Art of the Gurunsi Village and its Demise

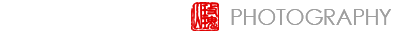

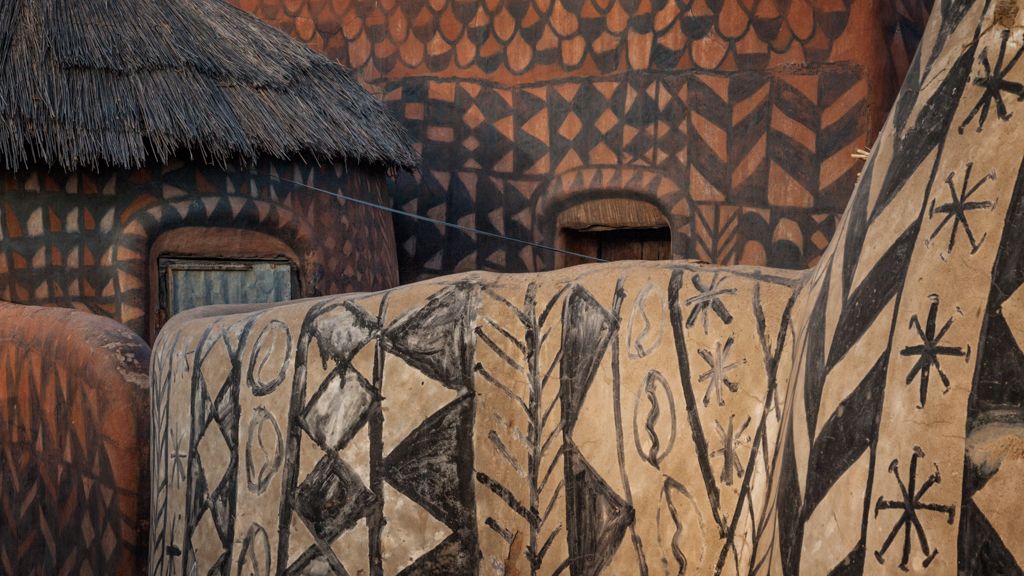

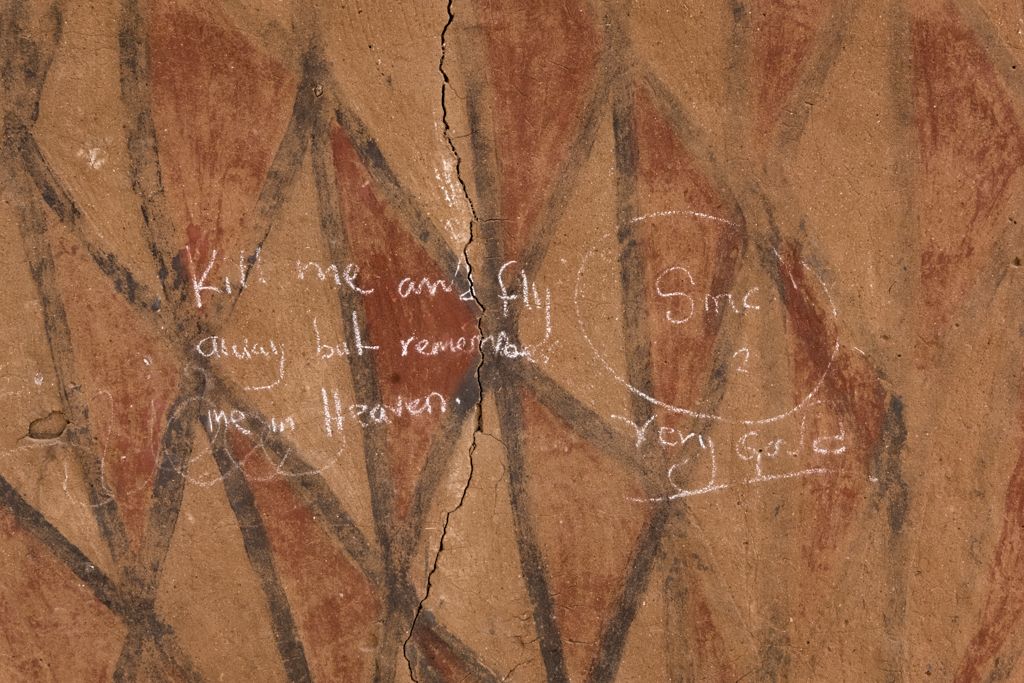

The Gurunsi are an ethnic group inhabiting parts of southern Burkina Faso and northern Ghana. Traditionally, the Gurunsi have been farmers and animists, living in large family compounds surrounding a central communal space. They have long been celebrated for the style and decoration of these compounds. The men of the village have been responsible for the design and construction, building up curving and flowing forms from multiple applications of clay over wooden support pillars and arches. The women have been responsible for the painted decoration of the walls of these structures, using intricate designs including geometric patterns and totemic animals, in a palette of natural colors dominated by white, black, and red. When I visited the Gurunsi village of Tiebele, in southern Burkina Faso, in 2010, the brilliant harmony of form, pattern, and color made the village a collective, lived in work of art. And in my photographs of Tiebele, I was interested in expressing how the striking designs and stylistic artistry of the Gurunsi people were fully integrated into the practical daily life of the individual and the community. But the Gurunsi are hardly isolated from the quickening pace of socio-economic and ecological change evident in West Africa as around the globe. In 2017, I visited another Gurunsi village, Sirigu, in northern Ghana and only a few miles from Tiebele across the border in Burkina Faso. (The first two thirds of the images here were made in Tiebele in 2010, and the last third in Sirigu in 2017.) This village had also been promoted as a collective work of traditional art but the reality that greeted me was rather more complicated. The constant weathering of the building materials meant that the traditional structures and decorations had to be regularly renewed, a process that required the commitment of significant collective time and resources. For a number of reasons—including prolonged drought conditions, the movement of men to cities for work, and the economic burden of providing materials and sustenance for those who do the work—that commitment has significantly waned in recent years, and the consequence is that the traditional architecture and decoration are fast disappearing. My guide, who had been in Tiebele a few months earlier than our visit to Sirigu, told me that the same thing was happening there. Here there were a few freshly painted structures that seemed to serve mainly as a draw for visitors, but elsewhere older structures were being remodeled or replaced with boxy structures of cinder block and cement and flat metal roofs, while the old designs that were still visible were faint and fading. New initiatives have been undertaken: There is a women’s collective selling art pieces and souvenirs, from which they hope to earn extra income that decorating their houses does not provide. But I wonder if tourists will come to buy their work if the traditional painted village has itself disappeared. There seems to have been no initiative for UNESCO World Heritage status, which might have brought publicity and resources to make preservation economically viable but now seems too late. One man with whom I spoke, a local who had returned home after some time working in a large city, said that he and others regretted the erosion of cultural traditions and skills but that there was resignation to the pressure of economic imperatives. At the current rate of change, it seems inevitable that within another few years the living art of the Gurunsi village will have passed into history.