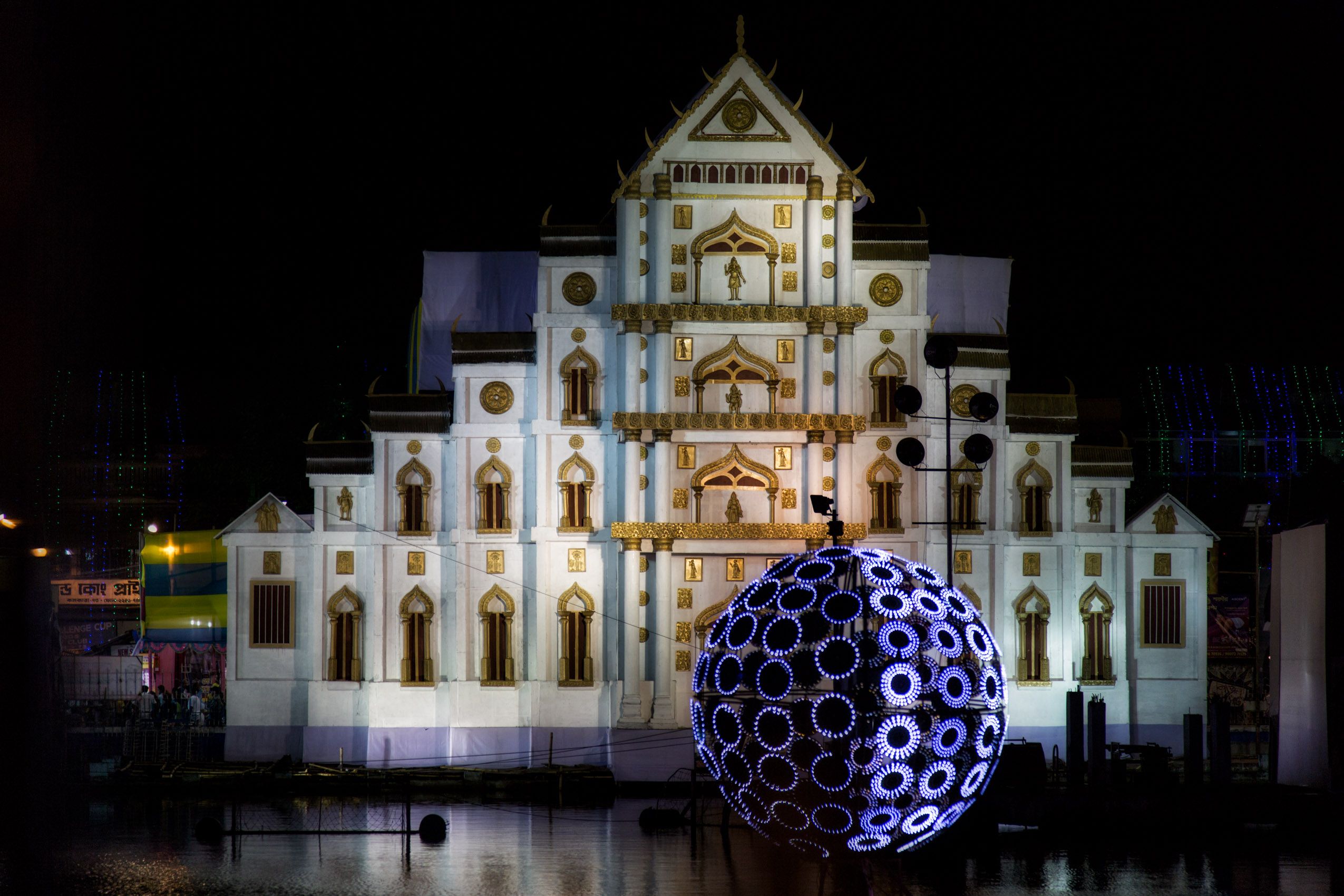

Durga Puja in Kolkata

Kolkata is India’s third largest city and Durga Puja is its biggest and most extravagant annual festival. Durga Puja celebrates the great Hindu goddess Durga, a female counterpart of Shiva, a destroyer of the forces of evil who protects and provides consolation to her devotees. Her conventional iconography represents Durga with eight (or ten) arms, each holding an object that symbolizes one of her attributes, and riding upon a lion or sometimes a tiger. Durga Puja lasts for more than a week, and throughout east India and especially in the great metropolis of Kolkata, it consumes the inhabitants and in effect dominates family and public life for the duration. Vast human and financial resources are consumed in planning and performing the festival, which these years involves intense organization along neighborhood lines and substantial corporate sponsorship. At the center of the celebrations is the creation of images (murtis) of Durga and her entourage. The goddess is invited to inhabit these idols temporarily, and their display becomes a focus of devotion and worship throughout the period of the festival, which concludes with the destruction of the images by immersion after the goddess departs from them. This cycle of creation, celebration, and dissolution can be seen to epitomize the essential rhythm of Hindu cosmology. This portfolio was made over the course of about ten days, and begins in the workshops of Kumartuli where families of potters craft the idols. Then the idols are transported to various sites around the city where they are installed on podiums and housed in temporary structures called pandals. The construction of these pandas is itself a huge undertaking, and neighborhoods and associations strive to outdo each other in the originality and lavishness of these temporary structures. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of them are installed around the city and its environs, and the citizens of Kolkata spend much of the festival in the activity of “pandal hopping,” seeing and making offerings to as many of the pandals as they can. At the installation and at other times during the period, Hindu priests make offerings to the murtis and devotees seek blessings. Much of this pandal hopping takes place during the evening, and requires extraordinary efforts at crowd control by the local authorities. The city becomes one gigantic fair, with numerous side shows and food courts temporarily installed around the pandals. Toward the end of the festival, married women smear red powder on the idols and on each other, as a prelude to the immersion. At the end, a seemingly endless procession of idols from pandals around the city is transported to the ghats along the river where, after the ritual departure of the goddess, these beautiful objects are cast into the water. Nowadays, out of concern for the potentially disastrous environmental consequences of this process, cranes and crews are standing by to quickly pluck the idols out of the water and unceremoniously dump them onto dripping heaps for subsequent disposal. To a non-Hindu observer, the whole glorious process and its melancholy end may seem like a colossal exercise in conspicuous consumption, but from within the ethos of Hinduism it is a profound annual lesson in the transience of the phenomenal world.