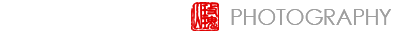

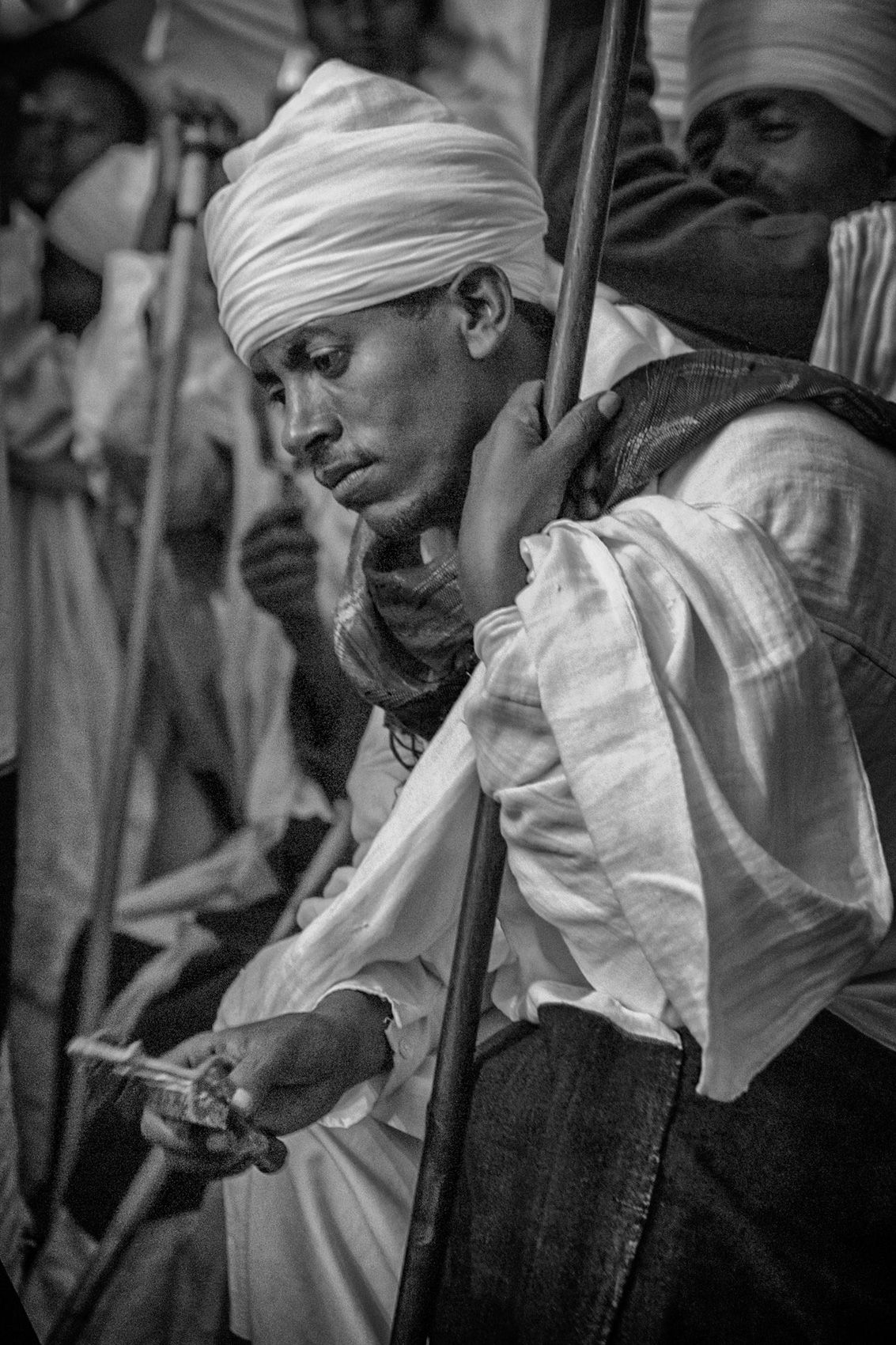

ETHIOPIA: Children of Solomon and Sheba: The Ethiopian Orthodox Church

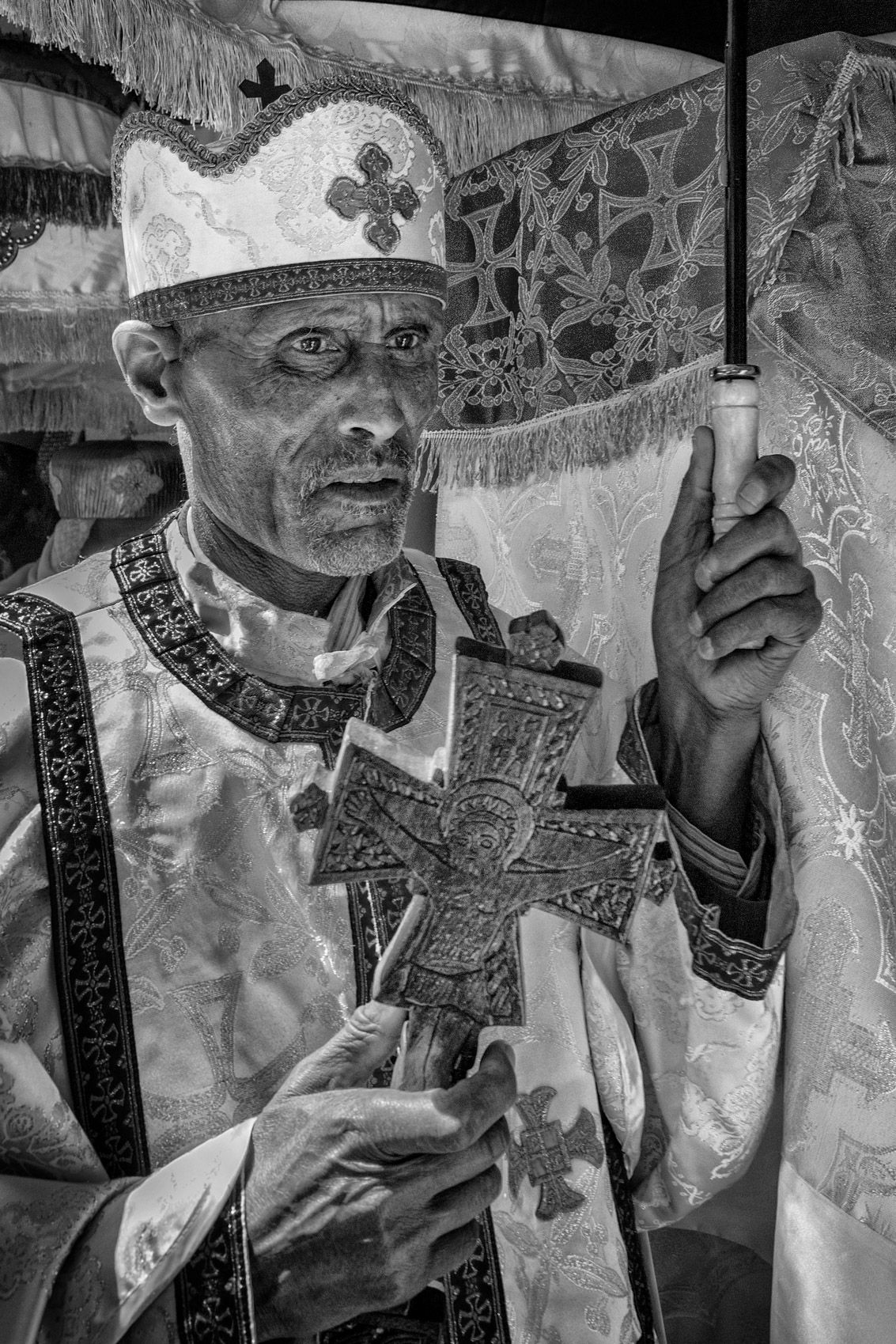

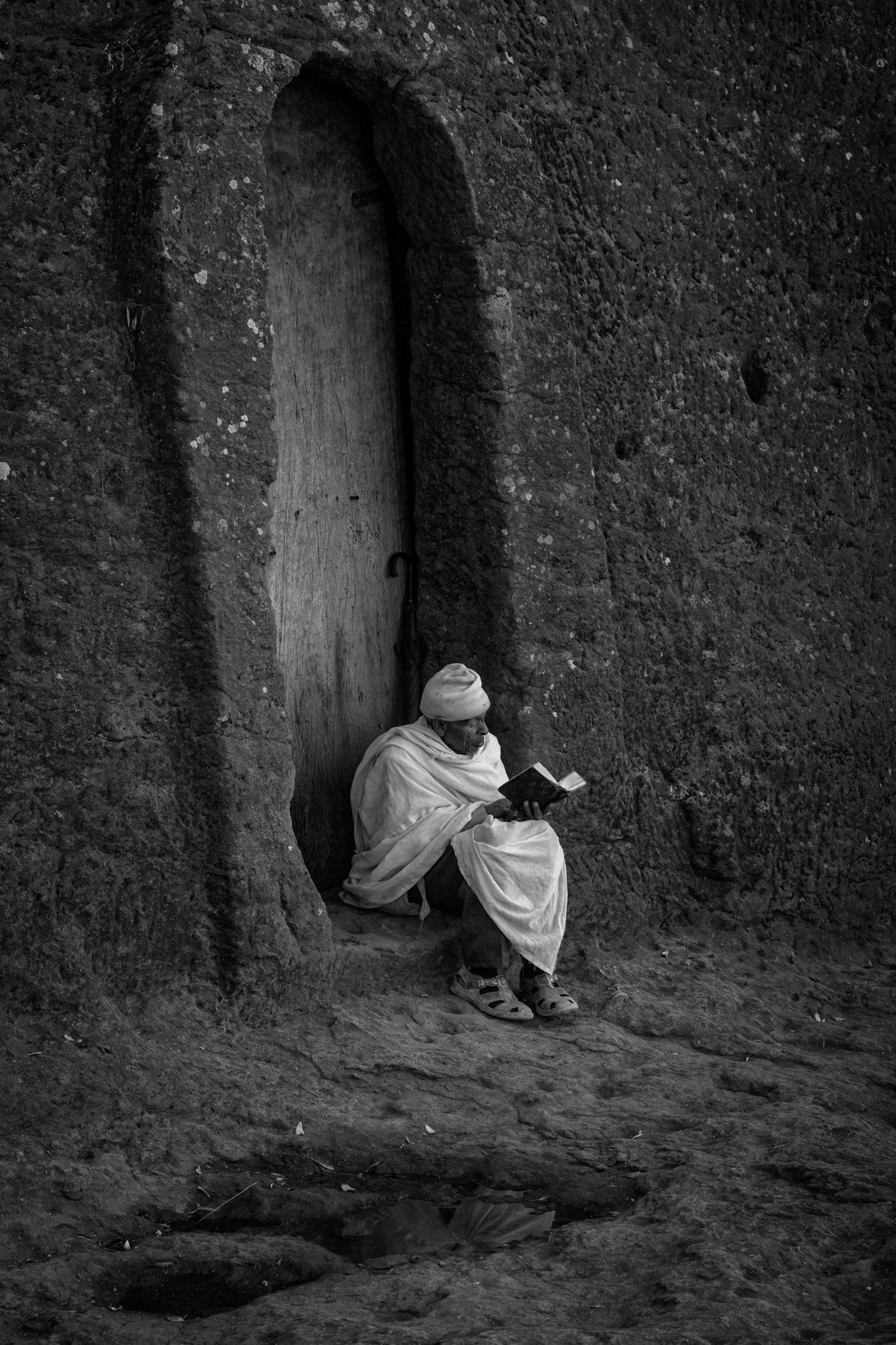

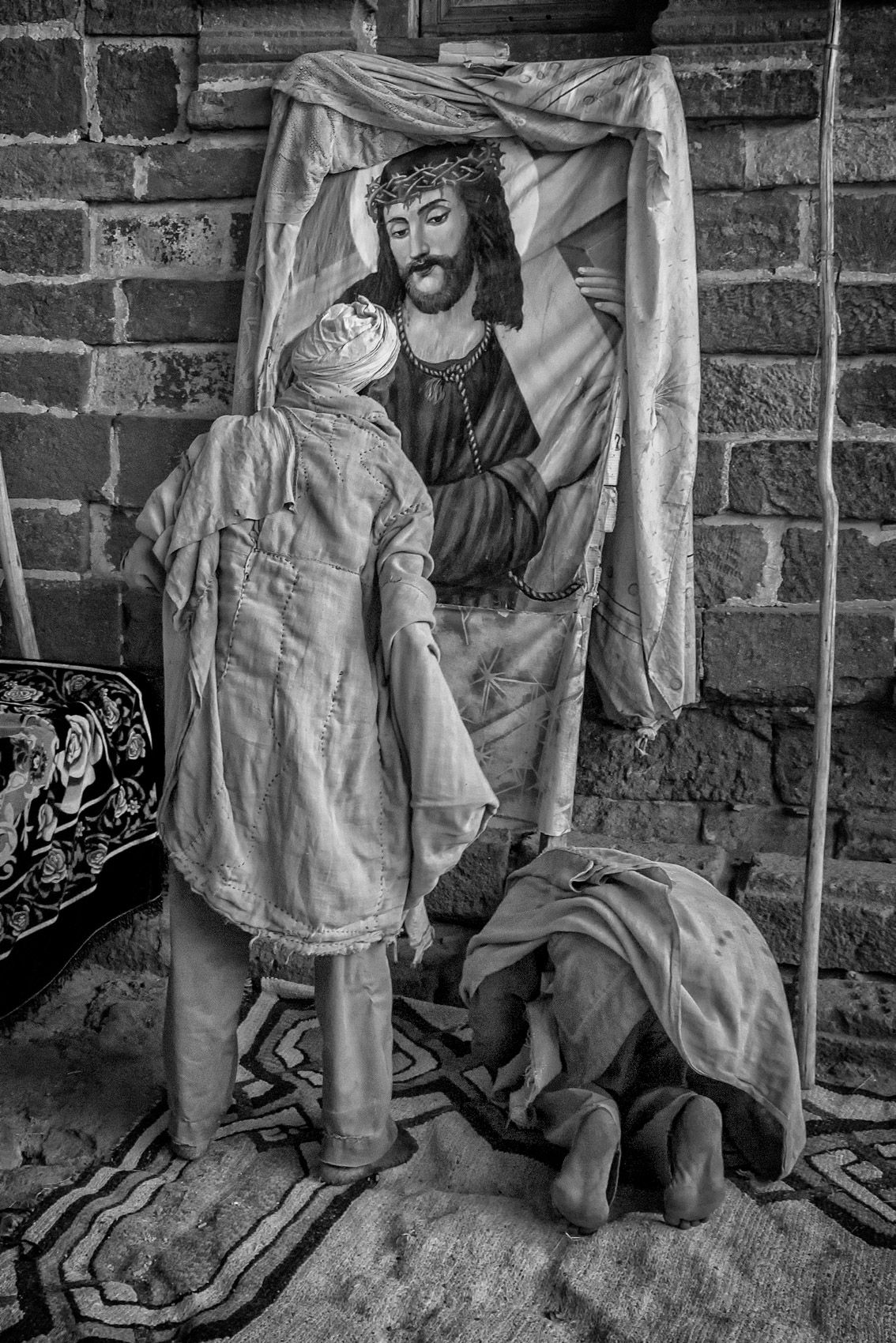

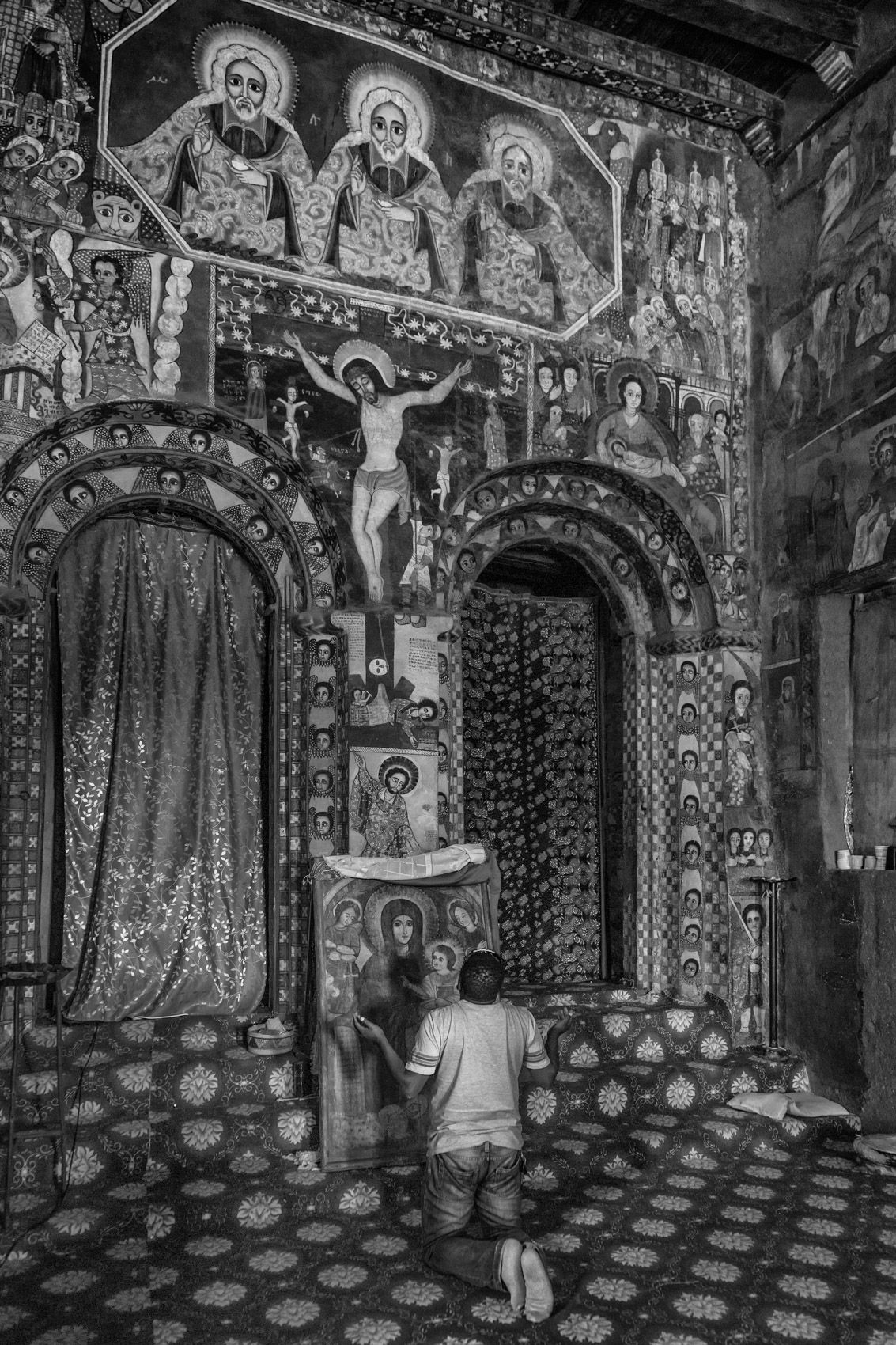

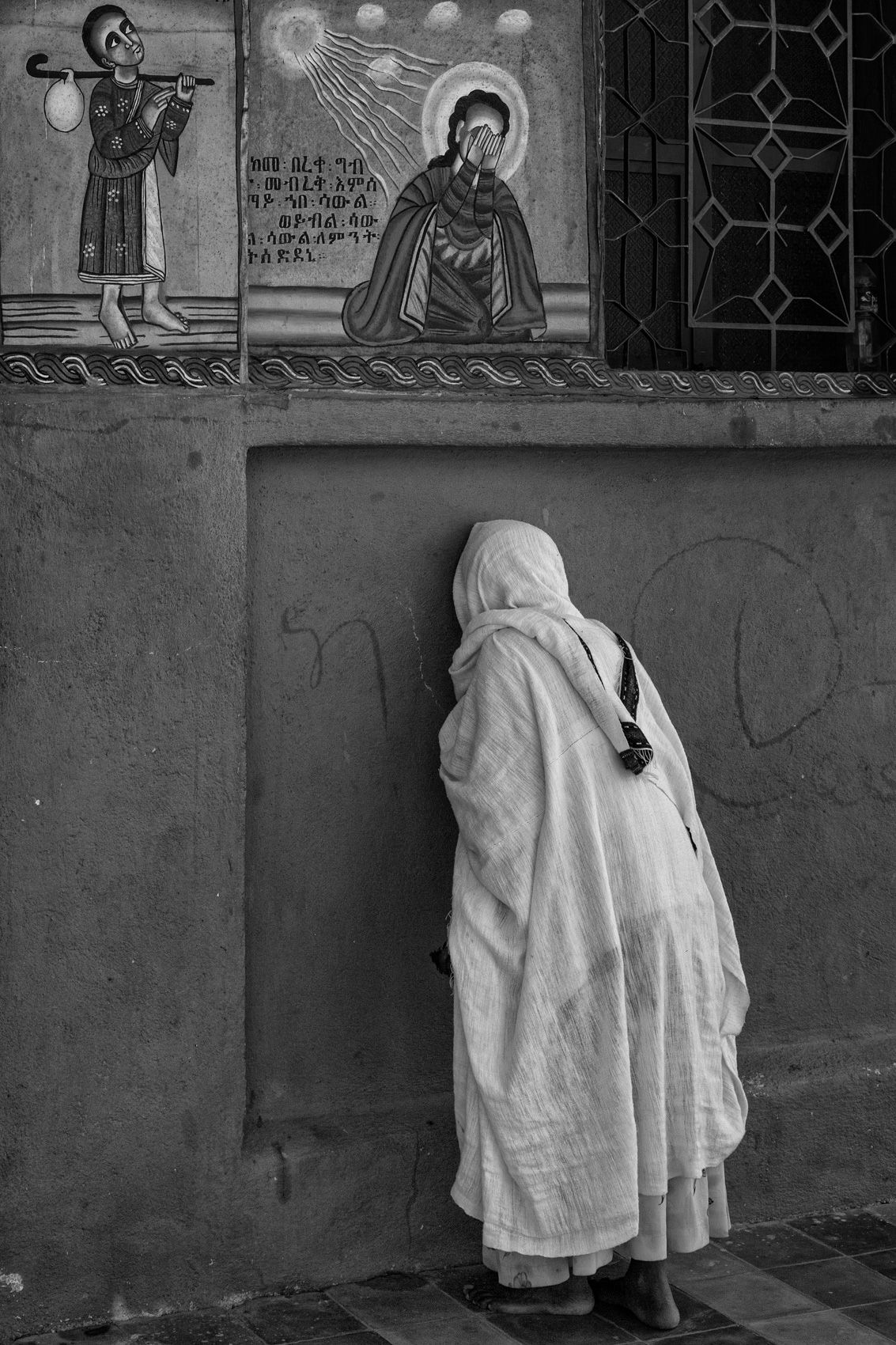

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church is one of the oldest Christian denominations, dating from the fourth century or earlier. Its many millions of adherents reside primarily in Ethiopia and among the Ethiopian diasporas in the United States and elsewhere. “Tewahedo” signifies adherence to the theological principle that Christ’s nature is a perfect and indivisible union of the human and divine. This theological doctrine it shares with other Oriental churches (the Coptic, Syriac, and Armenian) but not with the Christian churches of the West, which hold Christ’s nature to be dual. By the fourth century, Oriental Orthodox Christianity had become the established religion of the Axumite Kingdom in northern Ethiopia, and Axum remains the spiritual center of the religion today, although it is dominant throughout the highland plateau of the northwestern part of the country. Great authority is placed in the priesthood, and only priests may enter the inner sanctum of the church. Communion is restricted to those adherents who are considered pure in body and spirit and fast regularly; others are restricted to the outer part of the church. The church calendar includes a number of elaborate feasts, one of which—Timket, or Epiphany—is documented in some of the images in this portfolio. One of the most intriguing aspects of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church is its relationship to Judaism. Probably drawing upon a body of much earlier legends, a fourteenth century Ethiopian text called the Kebra Nagast establishes a genealogy for Axumite kingship and an origin for Ethiopian religion in the journey of the Ethiopian Makeda—the Queen of Sheba—to Jerusalem to experience the wisdom of King Solomon. Before returning home, she conceived a son who became King Menelik I. At the age of twenty-two, Menelik traveled to Jerusalem to meet his father; upon his departure for home, he was accompanied by a large retinue representative of all twelve tribes of Israel. They secretly carried with them the Ark of the Covenant, which many Ethiopian Orthodox believe still resides in a sanctuary in Axum accessible only to a single priest. Upon his return to Ethiopia, Menelik is said to have established a Solomonic dynasty and the practice of Judaism in Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church has a number of practices in common with Judaism that western Christianity does not, including male circumcision, rules on the slaughter and consumption of meat, and the observation of the Sabbath as well as the Lord’s Day. The venerated object in the sanctum of every Ethiopian Orthodox church is a tabot, a replica of the ark of the convenant. This portfolio constitutes a brief visual introduction to the clergy, laity, practices, imagery, architecture and physical setting of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. At the same time, I hope to communicate a more subjective perception of a religion deeply grounded in the region it dominates, one notable for its richly decorated churches and monasteries—many hewn out of rock or built inside caves or into alcoves—and for an ambience heavy with antiquity and mystery.